Some moments stay with us forever. This was mine. Thank you for connecting with Remember Me. 💔

~Sanela

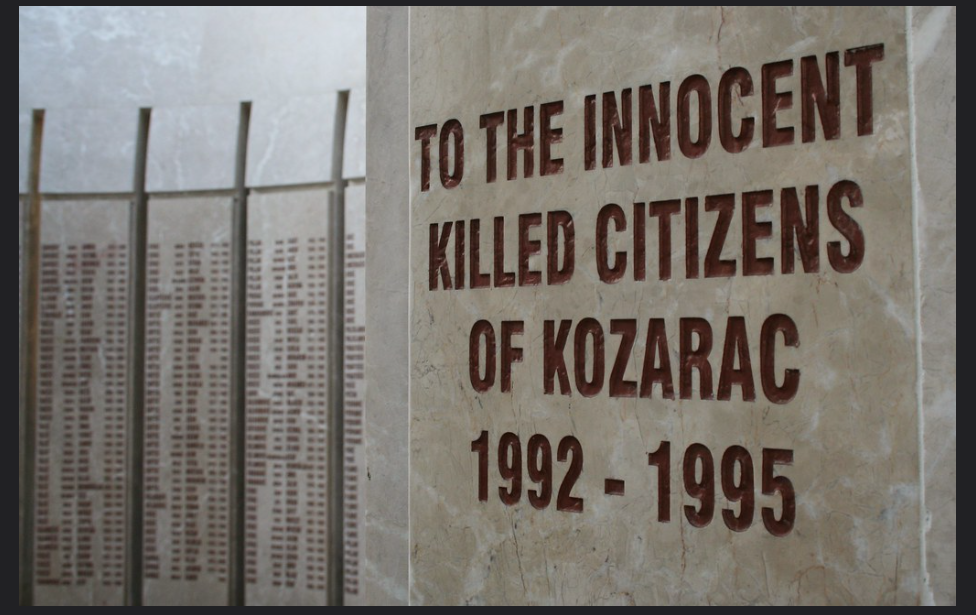

“The initial takeover included the attack on the town of Kozarac near Prijedor, on 24 May 1992, which included two days of artillery barrage and an assault by a mechanised brigade of troops. As a result, some 800 civilians out of a population of around 4,000 were killed.” ~Source

This time of year always brings up feelings of fear, overwhelming sadness, and a sense of not being wanted in the world or in life in general.

I witnessed the most horrible things happening to my family, friends, neighbors, and ultimately to me… I survived, but many didn’t.

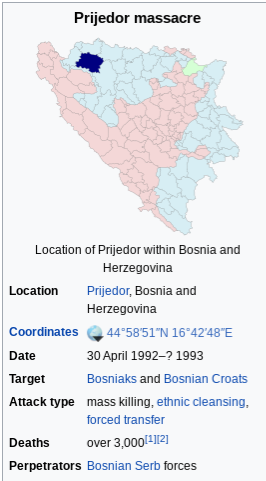

The year was 1992. It felt like hell on earth. In Europe, in a country called Yugoslavia, in a smaller place called Bosnia, and an even smaller town called Prijedor with its surrounding municipalities, everything was being torn apart. People I loved were consumed by evil: murder, torture, concentration and rape camps… Why?

This year marks thirty-two years since the attack on Kozarac.

I would like to share an excerpt from a book called Love Thy Neighbor: A Story of War by Peter Maass (An American Journalist).

I highly recommend this book. It is the first book I have read on the subject that describes Bosnia and Croatia in 1992 and 1993 exactly as they were, exactly how I saw it, but from a foreign person’s perspective.

Peter Maass worked as a foreign correspondent from 1983 to 1995, based in Asia and Europe. His articles have appeared in the Washington Post, The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic. His wartime dispatches from the Balkans led to his selection as a finalist for the 1993 Livingston Award for International Reporting. He is currently a magazine writer and lives in New York City.

Nationalist Serbs staged a nighttime coup to take over (my town) Prijedor. There wasn’t much fighting because the Serbs were well armed and there was no resistance to speak of. No one else was prepared for war. The man named Kovacevic organized the takeover.

In this excerpt, Peter Maass talks about the attack on Kozarac. Continue reading →

~Sanela

Sanela Ramić Jurich is a distinguished author and accomplished public speaker with a compelling background. Hailing from Prijedor, Bosnia, she entered the world in 1976, just as the complex tapestry of the Yugoslav war began to unfold in the early 1990s. Precociously navigating the challenges of those tumultuous times, Sanela was merely fifteen years old when the conflict erupted.

Her literary contributions, exemplified by notable works such as “Remember Me” and “Haunting from the Past,” stand as poignant testaments to her lived experiences during the war. These masterfully crafted books not only showcase her prowess as an author but also serve as powerful conduits through which she shares her personal recollections of the era.

Currently residing in the vibrant city of Chicago, Sanela Ramić Jurich has established a harmonious life alongside her two cherished sons. Her journey from the ravages of conflict to her present abode is a testament to resilience, determination, and the indomitable human spirit. Through her words and public addresses, she continues to captivate audiences, shedding light on her remarkable narrative and the broader lessons that can be gleaned from her compelling journey.

© Sanela Ramic Jurich

We took just a change of clothing with us. My father’s friend told us not to bother bringing anything else, because it would be taken away anyway. He was there to show us which truck was the safest one for us. My father had to go sit at the front of the truck with other men, and my mother and I sat in the back with women. It was so crowded; I half-sat on mother’s lap. They covered the truck with some brown tarp and off we went.

It was an unbearably scorching August day, the air thick with a suffocating heat that clung to our skin like a second layer. We were crammed together, pressed against one another like frightened animals seeking refuge, yet there was no escape from the oppressive closeness. The stench of sweat mingled with the acrid smell of fear as we huddled beneath a tattered tarp, trying to shield ourselves from the harsh sun that beat down mercilessly.

In that stifling darkness, my stomach churned with a mixture of nausea and anxiety. The bag that held our final remnants of belongings became my reluctant confidante, bearing witness to the physical and emotional turmoil within me. I retched into it, my body betraying me as the revulsion and dread threatened to overwhelm every fiber of my being.

Amidst the agony of the moment, a different kind of urgency surfaced—my desperate need to relieve myself. The very core of my being seemed to ache with the necessity, as if every discomfort I felt was a microcosm of the larger suffering we were enduring. Each passing second felt like an eternity, my bladder aching as if it held not only my own desperation but the collective weight of our shattered lives.

A little while later, we stopped moving. An armed soldier peeked in, waving his gun. He demanded someone to come out and be his helper. After a few torturous moments of hoping and praying I wouldn’t get to be the chosen one, the soldier pointed a gun at “Him” and demanded “He” be his helper for the day.

“He” was my very first crush and the inspiration for Johnny’s character in Remember Me and Haunting from the Past.

The soldier handed him a bag and ordered him to go around and make sure people put all their valuables into the bag.

That went on the whole ride: they would stop the convoy every few minutes to steal from us. People ran out of things to give, so they started putting nail clippers and toothbrushes into the bag.

The soldier ordered us to lift up our shirts to make sure we weren’t hiding anything there. And I wanted to die. At that moment, I wished I could just die. I would have preferred “Him” to see me dead rather than with my shirt lifted up. When he got to where I was sitting, he opened up the bag, but he closed his eyes. I had to lift up my shirt. The soldier watched the whole time; I figured he would rather humiliate me than kill me. But “He”… he must have seen my humiliation, and so he closed his eyes. He will never know how much that meant to me.

The pain we endured transcended the physical, burrowing deep into our souls. It was a pain that defied words, leaving only a raw and unrelenting ache. As the hours dragged on, I couldn’t help but wonder how humans could inflict such suffering upon one another. The soldier’s demands, the humiliation, the theft—it all seemed like a twisted manifestation of humanity’s darkest aspects.

And then, in the midst of this nightmare, my gaze met his for one final moment. In those fleeting seconds, a world of unspoken emotions passed between us. His eyes held not just the fear and despair that clouded our lives, but also an inexplicable shame—as if we were the guilty ones, as if surviving this ordeal was itself a transgression.

The last stop the convoy made (before reaching our destination) was on Koričanske Stijene on Mount Vlašić. The Serb soldiers pointed their guns at all the men they wanted to take out and kill. “He,” too, was one of the chosen ones. He was seventeen.

The Serb army slaughtered over 250 innocent, unarmed (civilian) men that day.

The rest of us were taken to the other side of the mountain and thrown onto a field of mines…

The memory of that day continues to haunt me, an indelible mark etched upon my soul. The Koričani Cliffs massacre wasn’t just a historical event; it was a canvas of suffering, painted with the hues of fear, anguish, and desperation. Even now, years later, the weight of that day presses upon my heart, a reminder that the scars of such horrors never truly fade.

© Sanela Ramic Jurich. All rights reserved.

There are stories that have the power to grip our minds and hearts, stories that force us to confront uncomfortable truths we’d rather avoid. One such story emerged from the pages of the enlightening book, Bourgeois Virtues, and has lingered in my thoughts ever since. It transports us back to July 15, 1995, when a chilling sequence of events unfolded in Srebrenica, forever tarnishing the legacy of a Dutch force operating under the United Nations’ command.

In an astonishing turn of events, the Dutch troops, stationed there specifically to prevent such atrocities, handed over a staggering number of 8,000 Muslim men and boys to the Bosnian Serbs. What makes this episode even more bewildering is that it happened without a single shot being fired. Instead of resisting the Serb demands, the Dutch forces, fearing their own casualties, willingly complied. It was a decision that would haunt them for years to come.

The gravity of the aftermath cannot be understated. A massacre ensued, claiming the lives of those 8,000 men and boys, as well as numerous women, children, and even infants in arms. This horrifying event stands as the largest massacre in Europe since World War II. Yet, what struck me the most was the lack of remorse or shame exhibited by both the Dutch army and the majority of the Dutch people. In fact, they vehemently denied any responsibility for the tragedy, instead pointing fingers at others.

Blame was cast upon the Canadians, who had previously controlled Srebrenica but had subsequently handed over control to the Dutch. It was argued that the Canadians should bear the burden of blame for what unfolded. The French, too, were held accountable for failing to provide necessary air cover. The Dutch commander himself was hailed as having made the right call, asserting that he chose not to open fire to avoid Dutch casualties. He had placed his trust in the Serb commander’s promise that none of the surrendered men and boys would be harmed; they would only undergo scrutiny to identify potential war criminals among them.

This narrative, however, raises a multitude of questions. Shouldn’t the Dutch forces have prioritized their duty to protect innocent lives over their own self-preservation? Why did they choose to believe the assurances of a known aggressor? How could they reconcile their actions with the devastating consequences that unfolded?

The Srebrenica massacre forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that even those tasked with upholding peace and justice can falter in the face of unimaginable circumstances. The Dutch army’s refusal to acknowledge their role in the tragedy speaks to a collective denial, a desperate attempt to absolve themselves of guilt. Yet, true progress and healing can only begin when we face the truth head-on, acknowledging our mistakes and working towards rectifying them.

This story, though distressing, serves as a reminder that we must hold accountable those entrusted with protecting human lives. It calls upon us to reflect on the complex web of factors that contribute to such failures and ensure that history does not repeat itself. As we delve deeper into the pages of our collective past, let us learn from these haunting stories and strive to build a future where the value of every life is unwaveringly upheld.

Unraveling the Disturbing Absence of a Narrative: Lessons from Srebrenica

The Dutch commander’s decision to comply with the Serb demands, avoiding potential casualties among his own forces, is often seen as the “right” choice. After all, he couldn’t have known that the Serbs would unleash a massacre, killing those 8,000 people. However, when examining the context, it becomes evident that certain aspects should have raised alarm bells.

The Serbs had a notorious reputation for their lack of honesty and had been conducting “ethnic cleansing” operations throughout the region for years. Given these circumstances, anyone who had pondered the situation for even a short while could have predicted the Serbs’ intentions. Moreover, the presence of UN forces in Bosnia was precisely due to the possibility of such atrocities. The Dutch commander’s priority seemed to be safeguarding his troops rather than preventing a potential genocide of Bosnian Muslims. This begs the question: if this army was unwilling to accept any casualties, could it truly be considered an army?

Reflecting on this narrative, it’s hard not to consider the contrasting reactions that would have ensued had an American commander been in charge. Outrage would have reverberated worldwide, with the American people demanding justice and the commander facing court-martial. The phrase “heads will roll” would have taken a literal meaning. However, let us momentarily set this aside and focus on a deeper aspect.

We, as humans, construct narratives to make sense of the world and our place within it. These stories allow us to explain ourselves to ourselves. From a vantage point across the Atlantic, the prevailing European narrative appears to be one of self-righteousness, boasting that they are the champions who will forever halt genocide. Having triumphed in World War II, they claim to have built the world’s first genuinely anti-racist society, positioning themselves above the Americans, Russians, and Chinese.

What strikes me about the events in Srebrenica and their aftermath is the absence of any coherent narrative. It lacks a compelling story, consisting merely of feeble, self-justifying excuses akin to those uttered by a petty thief caught shoplifting. There’s no substance, no shape, no arc. It’s as if Gertrude Stein’s famous phrase, “there’s no there-there,” perfectly encapsulates the situation. Curiosity led me to embark on a Google search, hoping to find a cohesive Dutch narrative, but to no avail.

I couldn’t help but wonder if, with enough searching, I would stumble upon a metanarrative for pacifism—a story that would rationalize the idea that regardless of the consequences for others, it is vital to ensure one’s own safety. Surely, such a narrative could exist, or perhaps another narrative that would reinterpret the same facts. The Germans, for instance, managed to create several narratives that encapsulate Nazism, even though they may not be entirely true. Similarly, the French skillfully crafted a narrative of a valiant resistance movement, overlooking the collaboration of certain individuals during the occupation. Criticism and scrutiny of these narratives have been relatively subdued.

The absence of a narrative, or rather the apparent lack of a need for one, is truly astonishing. It hints at a deeply rooted conviction that self-preservation is paramount, with an assumption that everyone shares this sentiment. It implies that there is no other way to feel and that those who claim otherwise are deceitful or misguided. Diverging from this mindset is deemed wrong. Apologies if I’m rambling, but this observation has troubled me for years.

For quite some time, I’ve heard claims that the US intervened in Bosnia and did what the UN failed to do. Now, the reason behind these statements becomes clearer. I must admit, it brings me a sense of relief to know that the American people, indeed, hold a different perspective. Because the absence of a need for a narrative to justify what should have been an unequivocal horror is far more disconcerting than the combined fears of fascism and communism.

“–I turn around and on the screen I see Chetniks (Serb Army) executing a group of men. Among them, my son, Azmir. I’m watching, but I’m not believing my own eyes. My heart stops, my jaw stiffens. Yes, it is my Azmir. They are shooting at his back. My child falls. Barefoot. He wasn’t even seventeen years old yet!” –Hatidža Mehmedović

Never forget Srebrenica, July 1995!!! #8372.

Today’s story takes us to Vukovar, Croatia.

Those of you who are not familiar with the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s might not have heard about Vukovar, Croatia. This town, located on the border between Croatia and Serbia, has been a scene of one of the biggest and most cruel war crimes in the current European history.

Around eight thousand people (mostly civilians) died during the fights, afterward during the Ethnic cleansing the majority of the Croatian inhabitants were either murdered or driven out of town. 99% of the city was destroyed, making Vukovar the first place in Europe so heavily damaged since World War Two. You can see how the city looked like during the battle here.

Once upon a time, there was a young couple named Majda and Siniša who fell deeply in love and were married shortly after they met. Siniša was a journalist, and Majda was a nurse who cared for the wounded. They lived in a beautiful small town called Vukovar.

In the spring of 1991, the siege of Vukovar took place and suddenly, the whole world knew the name of this little town. First incidents started off small: homes and shops were attacked … The Serbian Army surrounded Vukovar and the real siege started in August.

The city was defended by less than two thousand soldiers, while the Yugoslav Army (de facto the Serb one) had between 27 and 80 thousand soldiers attacking. The siege took 87 days until Vukovar was captured by the Yugoslav Army and proclaimed the Serb city.

Despite the chaos and danger of war, Sinisa and Majda found comfort in each other’s company. They would steal moments together whenever they could, stealing kisses in the dark corners of the hospital or holding hands during brief breaks in the fighting.

One day, Sinisa was badly injured by a shrapnel of a grenade destroying a nearby school and was rushed to the hospital where Majda worked. Majda was devastated to see the man she loved lying on a hospital bed, his body riddled with wounds.

She spent long hours by his side, tending to his injuries and offering words of encouragement. Sinisa, meanwhile, was overwhelmed by his feelings for Majda, knowing that she was the only person who made him feel safe in the midst of the war.

As Sinisa slowly recovered, he and Majda grew closer than ever before. They shared stories of their childhoods and dreams for the future, imagining a world where war was a thing of the past so they could raise their daughter in peace.

However, their happiness was short-lived.

The most barbarian part of the siege was when the hospital, clearly marked with the red cross, was attacked and captured. During the siege, the building was strafed over 800 times until it was eventually captured in November 1991.

Many of those who were wounded were killed directly in their hospital beds, others (255 non-Serbian workers and patients) were taken to the nearby village, Ovcara, where they were tortured and eventually killed and buried in the mass grave. Only one man managed to escape, his testimony helped to recognize this war crime.

During the Battle of Vukovar, Siniša Glavašević was regularly reporting from the besieged city. He is particularly remembered for a series of stories he had read to the listeners, that talked about basic human values.

On 18 November 1991, Glavašević sent in his last report, which ended with:

The picture of Vukovar at the 22nd hour of the 87th day [of the siege] will remain forever in the memory of the witnesses of this time. There are infinite spooky sights, and you can smell the burning. We walk over bodies, building material, glass, detritus and the gruesome silence. … We hope that the torments of Vukovar are over.

Glavašević disappeared shortly after this last report. He had been beaten and executed by Serbian paramilitary forces, along with hundreds of others between 18–20 November. In 1997, his body was exhumed from a mass grave in a nearby farm in Ovčara. He was 31 years old.

When I was fifteen years old, my whole life changed in a blink of an eye…

I truly believe that I survived for one reason and one reason only: to tell our story, to give a voice to those who don’t have it anymore. I was there as a witness. As a survivor, I have an obligation. I have to talk about what happened in Bosnia (former Yugoslavia), back in 1992, no matter the cost.

I truly believe that I survived for one reason and one reason only: to tell our story, to give a voice to those who don’t have it anymore. I was there as a witness. As a survivor, I have an obligation. I have to talk about what happened in Bosnia (former Yugoslavia), back in 1992, no matter the cost.

When most people think of the month of May, in their mind’s eye, they see: spring-time, renewal, rebirth, flowers, sunshine, laughter of children playing outside. I, on the other hand, see the beginning of an end. The beginning of unimaginable hell. Most specifically, I see a teenage Bosniak girl being raped by Serb paramilitary units. Her parents restrained behind a fence while she’s being raped repeatedly. After a while she’s left alone in a pool of her own blood …

My birth-town, Prijedor, Bosnia in 1992.

The other day, a ninety year old man, said to me: “You can’t possibly understand what those poor people in Ukraine are going through!”

“I’m Bosnian.” I replied quietly. Not giving him any more information than that, knowing full-well he knew about the war in Bosnia. He lived through the early 1990’s and was hearing about the horrible war in Europe on the news then, just like we’re hearing about Ukraine now. He didn’t say anything else to me about the subject. His confrontational demeanor changed instantly while the look on his face became a little softer as he understood why I was reluctant to carry on the conversation about the Ukraine in the first place, which he obviously craved so much in hopes of teaching this “ignorant, spoiled, young American girl” about the “real” struggles of the world. He assumed I was younger than I am, therefore, he assumed, I was spoiled and didn’t know anything.

I let it go. He wasn’t worth my time nor energy. He did, however, bring up the memories I just can’t escape no matter how hard I try.

I was born in Prijedor and in 1992, I was only 15.

You see, when other people talk about the war, what they think is happening is army against another army, buildings being blown-up, dead bodies on the street and screaming children … for those are the images that are constantly being displayed on our TV sets. But what I see–in my mind’s eye– behind those news-images is a little different and a lot darker. What I see and know first hand is truly happening is a young girl being raped repeatedly by men in uniform, while her parents are restrained behind the fence.

Let me tell you about her: she is scrawny. Tall, but skinny. Shy beyond comprehension. She only speaks when spoken to. Always quiet. She is beautiful, although, she doesn’t know it yet and she wouldn’t believe you if you told her so. She loves her school-mates and her teachers. She loves her parents and grandparents, her aunts and uncles and even though she has no siblings, she thinks of her cousins as her brothers and sisters. Most of all, she loves books. She reads about distant places and people she would love to visit and meet some day. She’s a day-dreamer. She is happy. She is your typical little girl. She could be your daughter or your sister. Maybe a cousin or even a girl you’re crushing on. She could be you.

She doesn’t know anything about politics and quite frankly, she doesn’t care about such adult matters. She thinks she’s in love with her childhood crush.

In 1992 her whole world crumbles. Her loved ones are being tortured and killed. Thrown away into concentration camps. She doesn’t know why. She’s being punished, but she can’t understand nor remember what it was that she did that was so horrible to be punished so severely … Continue reading →

Wed., November 22, 2017

(CNN) – Former Bosnian Serb army leader Ratko Mladic was sentenced to life in prison Wednesday after being found guilty of genocide for atrocities committed during the Bosnian war from 1992 to 1995.

Mladic was charged with two counts of genocide and nine crimes against humanity and war crimes for his role in the conflict in the former Yugoslavia from 1992 to 1995, during which 100,000 people were killed and another 2.2 million displaced. He was found not guilty on one charge of genocide, but received a guilty verdict on each of the other 10 counts.

Mladic was charged with two counts of genocide and nine crimes against humanity and war crimes for his role in the conflict in the former Yugoslavia from 1992 to 1995, during which 100,000 people were killed and another 2.2 million displaced. He was found not guilty on one charge of genocide, but received a guilty verdict on each of the other 10 counts.

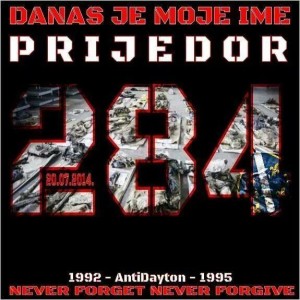

Today is a very sad day in my home town, Prijedor. We are putting to rest 284 bodies of innocents who were found in the largest mass grave in Bosnia. (Google Tomasica).

Today is a very sad day in my home town, Prijedor. We are putting to rest 284 bodies of innocents who were found in the largest mass grave in Bosnia. (Google Tomasica).

Although we are happy to finally be able to put to rest our family members who were lost to us for the past 21 long years, the pain is just as strong as it was back in 1992 when they were taken out of their homes and shot to death in cold blood by the Serb Army because they were not Serbs.

Today, I am with my mom and dad, my aunt Nefira, her son, Adnan who lost his dad, uncle, granddad and many cousins, I am with my uncle Ahmet and his son Velid, I am with my uncle Nuno and his dad, with my cousin Lejla, with my friend Ajla and her dad, I am with my friends Samir and Admir, with Pasa and Izeta…I am with the 284 innocent souls. May they all rest in peace. They will never be forgotten and their killers will never be forgiven.

During the Balkans conflict of 1992-1995, the Bosnian town of Srebrenica was declared a UN Safe Area in 1993, under the watch of the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR).

During the Balkans conflict of 1992-1995, the Bosnian town of Srebrenica was declared a UN Safe Area in 1993, under the watch of the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR).

In July 1995, General Ratko Mladić and his Serbian paramilitary units overran and captured the town, despite its designation as an area “free from any armed attack or any other hostile act”.

In the days following Srebrenica’s fall, more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were systematically massacred and buried in mass graves. Thousands of women, children and elderly people were forcibly deported and a large number of women were raped. It was the greatest atrocity on European soil since the Second World War.